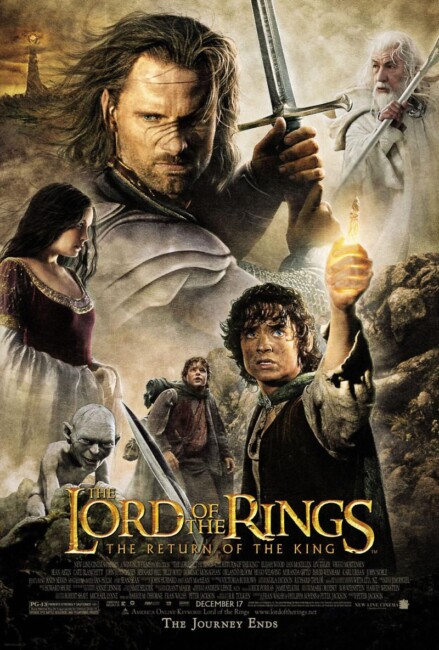

USA/New Zealand/Germany. 2003.

Crew

Director – Peter Jackson, Screenplay – Peter Jackson, Philippa Boyens & Fran Walsh, Based on the Novel by J.R.R. Tolkien, Producers – Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh & Barrie M. Osborne, Photography – Andrew Lesnie, Music – Howard Shore, Visual/Creature/Makeup Effects – WETA Workshop Inc (Creature Effects/Makeup Effects/Miniatures Supervisor – Richard Taylor, Visual Effects Supervisor – Jim Rygiel), Physical Effects Supervisor – Stephen Ingram, Production Design – Grant Major. Production Company – New Line Cinema/Wingnut Films/Lord Drutte Productions Deutschland GmBh.

Cast

Elijah Wood (Frodo Baggins), Viggo Mortensen (Aragorn), Andy Serkis (Gollum/Smeagol), Sean Astin (Samwise Gamgee), Billy Boyd (Peregrin ‘Pippin’ Took), Dominic Monaghan (Merry Brandybuck), Ian McKellen (Gandalf), Orlando Bloom (Legolas), John Rhys-Davies (Gimli/Voice of Treebeard), Miranda Otto (Eowyn), Bernard Hill (King Theoden), John Noble (Lord Denethor), Liv Tyler (Arwen Undomiel), Hugo Weaving (Elrond), David Wenham (Faramir), Cate Blanchett (Galadriel), Ian Holm (Bilbo Baggins), Karl Urban (Eomer), Paul Norell (King of the Dead)

Plot

Guided by Gollum, Frodo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee struggle on towards Mount Doom in Mordor. Unknown to them, Gollum desires the ring for himself and is sewing the seeds of distrust to separate Sam from Frodo with the intention of then betraying Frodo into the lair of the giant spider Shelob and taking the ring once he is dead. Meanwhile, reunited with Merry and Pippin, Gandalf realizes that Sauron is massing his forces against Gondor and rides to Minis Tirith to raise Lord Denethor, the steward of Gondor, to call upon the Riders of Rohan to help defend the city. However, Denethor has fallen into madness and Gandalf’s only choice is to defy his orders and call the armies himself. As Sauron’s orc armies’ mass, the numbers of men remain pitifully small and Aragorn realizes that their only chance is for him to claim the sword that will make him the king and rally to his side the cursed dead of the Dunwold.

I am a New Zealander. I say this, not simply out of any desire to regale you with personal biographic details, but simply because, as I write this (December 2003), it feels that the entire national identity of the country I live in is intertwined with the success of The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. The worldwide premiere of The Return of the King was held in Wellington, New Zealand (the capital city, where I lived at the time) and the entire country latched onto the event in a way that no other film has ever been greeted before in the history of motion pictures.

Lord of the Rings: The Kiwi Phenomenon

The premiere was an event that brought Wellington to a standstill. The entirety of the inner city was partitioned off and traffic diverted so that a parade headed by Peter Jackson and the various stars and technical personnel could proceed from a reception held at The Beehive (the country’s house of Parliament) to The Embassy theatre, one of the few remaining old-style 1930s cinemas, now owned by Jackson. The Wellington City Council and various charities had spent several million dollars refurbishing The Embassy in order to house the dignitaries for the one-off premiere screening. Outside, the city held a Return of the King party that went on until dawn (funded by the City Council to the tune of $400,000) with various street performers, outdoor screenings, speeches from all involved, an introduction from the Prime Minister and a giant Nazg’l mockup flying on wires over The Embassy. All of this was attended by reports of up to 400,000 people (a figure that seems a little high in that this is the actual population of the city itself). The country’s two main tv channels both suspended regular broadcast to give two hour plus live coverage from the scene. Air New Zealand repainted a 747 as The Lord of the Rings plane and conducted low-flights over the parade before departing the next day with the cast and crew aboard on a whirlwind tour of the various other premieres around the world. Elsewhere,

it seemed that one could not turn without being bombarded with Return of the King/Lord of the Rings mania. Every major business was exploiting Return of the King on billboards and tv commercials to a point of saturation overkill. The national postal service issued a series of Lord of the Rings stamps featuring the characters and various office blocks in Wellington were covered by giant-size banner recreations of these over 60 feet tall; just about every lamppost in Wellington flew a Return of the King flag; and at every airport in the country one could not literally walk 2-3 metres without encountering a poster that reminds one that New Zealand is Middle-Earth and that Air New Zealand (the national carrier) can transport you to Mordor, Osgiliath etc within 40 minutes; while Wellington Airport outdid everybody by including an exhibit of various sets from the series along the departures walkway, had a prominent sign that welcomed international travellers to Middle-Earth, and even a 30 foot tall mockup of the Gollum holding the Ring mounted on the exterior of the main terminal.

One defies anybody anywhere to come up with another film that has been greeted with such enthusiastic nationalistic fervour. There have been big event premieres before, but hardly any that can have not only claimed to have brought an entire country to standstill, but to have also been the basis of one city’s refurbishing its own image and an entire country mounting a tourist campaign. The phenomenon is more akin to the national celebration that an international win at a sporting event or even military parades are greeted. Personally, I have an intense dislike of patriotism and national pride (in any country), so it has been an interesting experience to stand at arms length from Return of the King mania and simply observe the phenomenon.

To understand what is all about one has to look at the isolated nature of New Zealand as a country. New Zealand has a population that only topped the four million mark in 2003, a land mass that consists of two and a bit islands at the bottom of the Pacific and is two hours flight from the nearest neighbouring country. It is a country that is placid and dull – the standard of living is good, the environment is clean, there is no poverty, police don’t carry guns, many still don’t lock their doors and the annual murder rate can probably be counted on the fingers of two hands. The downside of this is that imported goods are expensive and the country is frequently regarded as too trivial for the rest of the world to bother – movies around this time took on average three months to one year to be released theatrically after their US premiere, if at all.

More importantly, it is rare that anything that happens in the country makes ripples on the wider world stage. However, The Lord of the Rings was one such occasion when something from New Zealand did. It was one occasion where a film did not merely get some attention and acclaim in the international marketplace, as say other works like Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993), Peter Jackson’s own Heavenly Creatures (1994), Once Were Warriors (1994) and Whale Rider (2002) did, but one that did so in a spectacular way. New Zealand is extremely green in terms of international movie-making – there is barely one international production that comes here to shoot a year and the presence of big (or even not-so-big) name stars in town is a rarity.

So when an effort such as The Lord of the Rings garners such international acclaim, wins Academy Awards, becomes one of the biggest box-office sensations of the last two respective years and develops an extraordinary fan following, it is something that is not just a film event but also lifts the national identity with it. Moreover, The Lord of the Rings feels like a project that every single New Zealander was involved with in some way. During principal shooting, Wingnut had the biggest staff role of any employer in this country. As one friend commented to me: “I don’t think there is a single person in this country who can not say that they themselves were or did not know someone who was involved in the making of The Lord of the Rings.” (Personally, I can count at least three friends that work for the WETA Workshop and about five others that did extra work on the film).

In standing back at arm’s length from the national pride and patriotism associated with The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, one begins to question whether it is a good thing. Much of it feels like a nation that has become drunk and lost all rational sensibility at the merest hint of Hollywood glamour and big-name stars. There seem an extraordinary number of people happy to climb aboard the Lord of the Rings bandwagon and blow their own trumpets. I do remember the furore that erupted when Peter Jackson’s Braindead/Deadalive (1992) was named the Best Film of 1992 by the New Zealand Film and TV Awards and how people were shocked that a gross-out splatter comedy could be regarded as the country’s best film that year. Back then Peter Jackson was an uber-geek making B-budget horror films, a genre not exactly highly regarded by the arts establishment, yet the same arts crowd are the ones clambering aboard the Lord of the Rings bandwagon and hailing Peter Jackson’s genius.

The more you look behind the dazzle and patriotic fervour, there is much that you can start to question. Beneath the glamour of the The Return of the King parade, Wellington city mayor Kerry Prendergast passed a law to arrest all homeless – specifically one harmless man who would sit in the streets clad in a blanket – presumably so that the sight of one rather smelly man might not offend international celebrities. While Prime Minister Helen Clark greeted the street parade and held a reception for Jackson and the stars, forgotten in all of this was the fact that her Labour Government actually opposed the tax cuts that were passed in 1996 by the previous National Government. Much and all as I detest the damage they wrought on the country, the Bolger-Shipley National Government did at least set the deal up and should be given credit where credit is due, whereas in fact the opposition party never even received an invite to the premiere screening.

Perhaps the most amazing thing to emerge out of the national Lord of the Rings frenzy, is the way that the films were financed. In an extraordinary move, the government created a special tax shelter for the film that allowed New Line Cinema (a US-based company) to reclaim nearly an estimated 50% percentage of the films’ $300 million budget. (Such a move was criticized as providing unfair competitive subsidy by the OECD). While I think promoting local film opportunities is a great thing, let’s face it – the reality of it is that Hollywood executives are not coming to New Zealand because they like the look of the scenery, but rather because the government is bending over to turn the country into the Hollywood equivalent of a third world sweatshop – one where the low return on the Kiwi dollar against the US allows money to go further and where a non-unionised film industry means they are not so tightly bound by the same rules and regulations there are in the US.

It feels like an occasion where fame and Hollywood lights have dazzled officials and the public alike to the extent they have created a public blindspot – you can guarantee if say McDonald’s or some other less glamorous American franchise were afforded such tax breaks (let alone had the city council paying half a million dollars for their premiere party), the public furore would be enormous; because it is the film industry, nobody questions a thing. The government then further announced that similar tax shelters would be available to any Hollywood film budgeted higher than $50 million that came to New Zealand shores to shoot. Elsewhere other people rushed to build new film studios, while the government personally subsidized Peter Jackson building a new sound editing facility.

After the Hollywood glamour clears from people’s eyes, some people may end up questioning the dubious economics of it. While many government sources have been quick to justify the tax shelters in terms of what Lord of the Rings is bringing in tourism, they have also had to shrug and admit that there is no economic costing available on whether this is happening and that tourism alone is unlikely to ever make such money back. While the tax shelters were justified in terms of creating local jobs, you wonder who they ended up benefiting bar the New Line shareholders – even Peter Jackson’s own WETA effects facility had problems keeping its staff on the payroll once the trilogy ended.

The downside of this was that, while everybody has Hollywood stars in their eyes, the local homemade film industry was quietly trying to struggle to stand on its own feet. The amount of money that New Line reclaimed in tax breaks and took out of the country was ten times more than the entire budget of the New Zealand Film Commission, which funds local filmmaking. The Film Commission’s budget has been slowly shrinking in recent years – the great irony of this is that the money that Jackson obtained from them to complete his first film Bad Taste (1988) would probably be something unavailable to him today. The belief that there is money to be made signing onto US productions has also turned out an industry of technical talent that is now looking to make the big money, which has in turn pushed up the costs of impoverished local filmmaking, most of which does not break even as it is.

Perhaps the greatest upshot of the tax shelters has simply been the invisible cost of boosting national pride, of lifting the national spirit out of its perpetual sense of international underachievement and allowed it, if only for a brief time, to sail with glory upon an international stage. There has been little in the way of sour grapes and bitching from the average person on the street about the way that the taxpayer money has been spent, rather the public has seemed to have passively encouraged this as one of the costs of the great national endorphin rush that was Lord of the Rings.

More crucially, Peter Jackson, who spurned the glamorous life and the Hollywood rat race, who refused to attend gala premieres in a tuxedo and tie and prefers to make his films in his hometown, is seen in all of this, rightly or wrongly, as someone who has refused to lose touch with his roots. Whereas other local directors such as Jane Campion, Roger Donaldson, Lee Tamahori and Vincent Ward have gone onto considerable success in the international marketplace, they have had to leave New Zealand to do so. Peter Jackson has assiduously refused to and the difference is immediately apparent – Campion, Tamahori et al, while celebrated for their achievement, remain distant figures; Jackson, though spurning publicity, has gone onto become what was described by one gushing reporter as “the most popular man in the nation” and the trilogy’s success is seen as a local hero’s triumph.

In all of the Return of the King hoopla, you kept wanting to shake people and remind them “It’s only a movie.” One suspects that in a couple of years time when Lord of the Rings mania has died down and fickle audiences everywhere have gone onto the Next Big Thing that all of this – renaming a country Middle-Earth and predicating an entire tourist industry on the popularity of three films – is going to seem faintly ludicrous. I mean, does Tunisia have an ongoing tourist boom due to the popularity of George Lucas’s Star Wars films? Are there still tours held of the locations for The X Files (1993-2002, 2016-8) in Vancouver now that the series has gone off the air? I suppose in all of this the worst thing that could have happened was that The Return of the King ended up being a flop, as was the case when Peter Jackson made The Frighteners (1996), when similar national expectations resulted and the film fizzled.

The Review Itself

Surrounded by such hype and expectation, being bombarded with Return of the King merchandising and advertising every time that one walked down the street, it feels difficult to write an objective review of the film itself. Let professionalism try to prevail … First of all let me say the first two films, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) and The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002), were stupendous epics. With them, Peter Jackson conducted filmmaking and storytelling on a scale that no other director had accomplished before. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King brings the saga to a close, but it also feels the weaker of the three films.

In regard to the J.R.R. Tolkien source, each film has made various changes to the books, more as the saga goes on, and in the case of The Return of the King, this is the most variant of the three. The moving of Frodo’s venture into Shelob’s lair from The Two Towers to here (according to Jackson because “not much happened to Frodo and Sam in The Return of the King otherwise”) is no particular problem. More so though is the complete rewrite of the ending. The saga ends with Frodo and the hobbits returning to the Shire and Gandalf booting out Saruman who has taken refuge there. (I will not even venture into the contentious issue of the piqued Christopher Lee and his seven minutes being cut from The Return of the King, except perhaps to say that I would far preferred to see more of Christopher Lee than any of the elf scenes, particularly anything involving the talent-handicapped Liv Tyler. But then one supposes that Peter Jackson had to satisfy the romantic element and the substantial teenage girl audience that wets their panties at the sight of Viggo Mortensen).

Perhaps in that The Return of the King has varied so widely from the source text, there is the sense that the film is not so much following J.R.R. Tolkien’s saga as it is improvising on its own and as such often works far less effectively as a story. There are no complaints with the story strand following Frodo, Sam and Gollum’s journey to Mount Doom. This tells the story just the way one expects it, with appropriate heroism, struggle and triumph. Sean Astin gains his heroic strength magnificently, although it is Andy Serkis (and WETA)’s performance as Gollum that shines through and steals the bulk of The Return of the King. Some of the other characters in the story seem disappointingly part of the scenery – Ian McKellen’s Gandalf never gets up to much, while David Wenham still makes a watery and weak-jawed Faramir and feels miscast. Peter Jackson and his co-writers at least keep general faith to the book. For all that The Return of the King was criticized for its multiple endings, which one did not feel was a particular problem, most of these are there in the book (and in fact take place over a much longer time period).

The greater problem with The Return of the King is that it feels a more disparate story. The big set-pieces of the venture into Shelob’s lair and Aragorn’s raising of the dead of the Dunwold feel for the first time in the series less like parts of a journey that is a greater piece of the whole than they do merely episodic adventures – the sort of random encounters that one might come across in a game of Dungeons and Dragons. The wowing point of The Two Towers was Peter Jackson’s staging of some genuinely spectacular battle sequences.

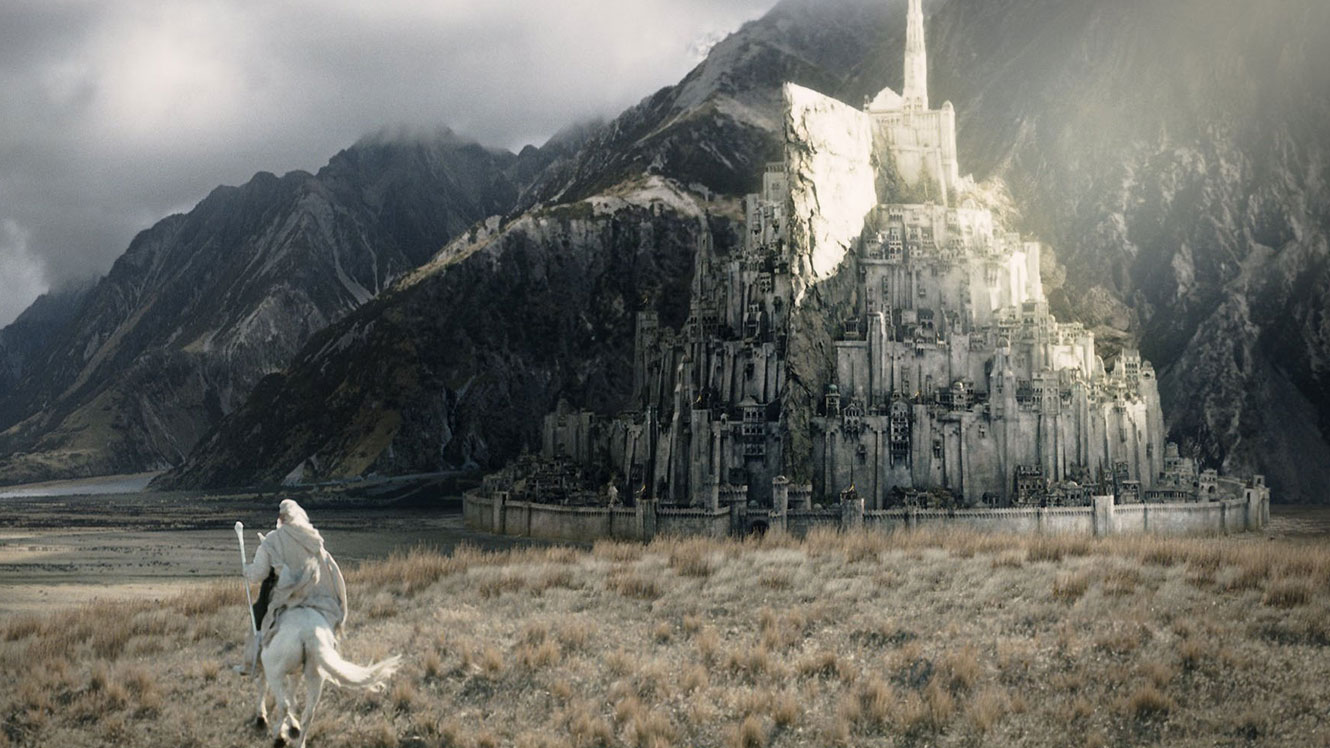

The onus on The Return of the King is naturally to have to up the scale of these. Arguably, The Return of the King does, but it also spreads these out into three entirely different sequences and there is ever so much the sense that Peter Jackson is trying to do the sequel thing and outdo the predecessor by simply offering more of what worked the previous time. What worked so well in the Battle of Helms Deep sequence in The Two Towers was the stunning scale of the battle sequences, the sense of the destiny of the entire world at stake and of a pitifully tiny few group of people facing an overwhelmingly huge army of evil. There are few stories/films that convey such a sense scale, of tiny vs big and of the triumph of good at the end. The Return of the King seems to have lost some of the edge by comparison – there is not such a sense of monumental destiny being fought, just the hopping from one battle sequence to the next. Certainly, Jackson expectedly wows audiences with the scale of things – the siege of Minas Tirith with the men of Gondor firing catapulted chunks of masonry down onto the orc armies, and especially the arrival of ‘oliphants’ and the seat-edge sequence where Legolas brings one of them down, and the fabulous sequence where Miranda Otto’s Eowyn faces the Witch King. It is just, these individual moments aside, that the sequences never carry the same enormous emotional charge as they did in The Two Towers.

The real triumph of The Return of the King is perhaps not even the culmination of the story or the eventual victory of good, but the emergence of Peter Jackson as a filmmaker with few equals. Fifteen years earlier, Jackson emerged with the no-budget splatter film Bad Taste and subsequently went onto make a trilogy of hysterically funny gross-out splatter films with Meet the Feebles (1990) and Braindead/Deadalive. With these, Jackson seemed to be shaping up to be a talented and very funny, scatologically obsessed director in the low-budget end of the late 1980s splatter film genre. Jackson’s breakthrough came with the internationally critically acclaimed Heavenly Creatures which, one’s misgivings about the film aside, gave Jackson critical credentials and placed him on the path towards becoming a filmmaker who readily leapt aboard the new CGI technology bandwagon. Jackson went a little astray with his next film The Frighteners, which tried to graft CGI onto a Peter Jackson horror comedy and was not particularly funny. Jackson then found his wings with The Lord of the Rings, which has become the most popular fantasy series in the world and may well even come to supplant George Lucas’s Star Wars series for fan audiences.

If you consider other filmmakers who have come from similar backgrounds, nobody else has conducted such a meteoric rise to the very forefront of filmmaking – Stuart Gordon made the wittily disgusting splatter comedy Re-Animator (1985) but has yet to have made anything that has been a mainstream success and has not had a film released to theatres for at least a decade; Tobe Hooper had a groundbreaking success with the no-budget The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), went onto the big success of the Spielberg-produced Poltergeist (1982), but has since then frittered it away until he is now working directing tv pilots; John Carpenter came from a low-budget background and had a big horror hit with Halloween (1978) but into the 1990s all of his work has been lacking in an essential something; while George Romero was once seen as the great white hope with efforts like Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978), but into the 1990s was barely making films any more. The nearest equivalent to what Peter Jackson has achieved might be Sam Raimi who emerged with the high-energy splatter effort The Evil Dead (1981) and, after more than a decade’s unevenness and uncertainty, finally had a big hit with Spider-Man (2002), the only film that outdid The Two Towers at the box-office in 2002. There is not a single other director that has come from a low-budget splatter or horror background, even amongst those with films that were far more successful in the international marketplace than any of Peter Jackson’s splatter comedies, who have ever made such an extraordinary rise out of the horror ghetto. Not to mention the fact that, unlike these other, Jackson is a Hollywood outsider to boot.

The difference it seems is in Peter Jackson’s constant ability to keep improving what he does. You can contrast Peter Jackson to George Lucas who made Star Wars (1977), which for several years became the most popular film in the world. Lucas though reacted to the success by running away from it, spending the next twenty years in retreat in his Marin County ranch before eventually returning to the saga with completely underwhelming results, showing that instead of learning and building on what he had done before, he had lapsed in the interim and that what he was producing was mawkish and banal fantasy product little more above the level of a children’s cartoon show. Though principal photography of the Lord of the Rings was completed in 2000, Jackson continually reshot and digitally tinkered with the films, even right up until a week before the premiere of The Return of the King. You can chart his clear progression as a filmmaker all the way from Bad Taste through The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, as someone who began as an enthusiastic fanboy filmmaker with a Bolex seeking to recreate the trick effects from Cinefex magazine on a used shoestring budget to someone who has produced an epic that has stunned the whole world. About the time of Heavenly Creatures and The Frighteners, Jackson seemed a filmmaker who was pushing the visual effects trickery at the expense of the film, something that has gotten many other directors cresting the CGI boom down.

Even when The Fellowship of the Ring came out, the film seemed slightly awkward, with Jackson displaying more interest in the spectacle but seeming slightly hesitant when it came to the actors and characters, preferring instead to allow the effects to tell the story on their behalf. By the time of The Return of the King, we have a filmmaker who is fully in command of the medium – someone who pushes the spectacle in a way that wows audiences, but never draws one to the artificiality of it; and of someone who can tell an epic story and has allowed its human strengths to come forward and carry it. Look at the path characters such as Sam, Merry and Pippin have taken from Fellowship, where they were little more than comic foils, to here where you fully converse with their sense of being tiny characters fighting heroic odds with all they have.

Equally, The Return of the King has an extraordinary visual sweep to it – there is the breathtaking moment that the camera sweeps through the air across mountain peaks to follow the lighting of the signal fires, or the slow-motion drift of the eagles as they snatch Frodo and Sam from the burning fires of Mordor. It is here, in the sense of epic sweep and visual mastery to the point that one no longer cares whether they are watching effects, people or a melange of both, that shows Peter Jackson’s emergence as one of the directors at the forefront of filmmaking. This was something that Jackson pushed to even greater heights with his subsequent film King Kong (2005).

At the 2004 Oscars, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King won eleven Academy Awards, including Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Special Effects, Best Art Direction, Best Song and above all Best Picture, the first fantasy film to do so. It is unclear though exactly how many of the voters were voting to give an award to the trilogy as a whole or whether they felt that The Return of the King genuinely was the best film of its year.

Peter Jackson subsequently returned to Middle-Earth with The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (2013) and The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies (2014). This was followed by the Jackson-less tv series The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power (2022- ). Also of interest is the earlier animated adaptations The Hobbit (1977), The Lord of the Rings (1978) and The Return of the King (1980). Tolkien (2019) is a biopic of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Peter Jackson’s other films include:- the zero-budget splatter film Bad Taste (1988); the hilariously adult take on the Muppets Meet the Feebles (1990); the gore-drenched zombie comedy Braindead/Deadalive (1992); Heavenly Creatures (1994), based on a sensational true-life murder in 1950s New Zealand; the flop ghost comedy The Frighteners (1996); and the afterlife film The Lovely Bones (2009). Jackson has also produced District 9 (2009), The Adventures of Tintin (2011) and written/produced Mortal Engines (2018).

(Winner for Best Supporting Actor (Andy Serkis) and Best Musical Score, Nominee for Best Supporting Actor (Ian McKellen), Best Special Effects, Best Makeup Effects and Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 2003 Awards. No. 1 on the SF, Horror & Fantasy Box-Office Top 10 of 2003 list).

Trailer here